Social Security has been a cornerstone of American retirement for nearly a century. A federal program born on August 14, 1935, from the financial crisis of the Great Depression to provide a foundational safety net for older Americans who are no longer able to work due to age or disability. Yet, despite the profound impact on millions of lives, the Social Security system is frequently obscured in a fog of misunderstanding, political rhetoric, and persistent myths. This complexity often leads to anxiety and poor decision-making during retirement planning, leading to costly mistakes and the loss of potential additional benefits. For workers of all ages, from those just starting their careers to the baby boomers on the cusp of reaching retirement age, understanding the realities of this system is critical for planning a stable financial future.

Social Security has been an objectively successful government program. It prevents tens of millions of adults age 65 and older from living below the poverty line. It has lowered the national poverty rate from roughly 37% to 10% percent. In fact, for 90% of the population, Social Security payments are their most valuable asset, more valuable than cars or homes. For beneficiaries, the Social Security lifetime benefit is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. The fact that this benefit is such a critical source of income for the vast majority of retired or disabled individuals makes it even more crucial for people to have the best available information when making decisions about when to claim retirement benefits.

That said, gaining a clear understanding of Social Security can be difficult, thanks to the many myths that continue to circulate. Throughout this guide, we address several persistent Social Security myths, such as the idea that the system is “going broke” or that immigrants are draining Social Security coffers.

Myth 1: “Social Security Will Cease to Be Solvent and Will Not Be Available for Me When I Retire”

Perhaps the most enduring myth is that the Social Security system will completely run out of money and collapse, leaving younger generations with nothing when it is their turn to retire. This misleading narrative does not accurately portray the financial strength of the program, and it ignores the relatively straightforward solutions to shore up funding for it.

To understand why this myth is so pervasive, it’s critical to understand where the money for Social Security comes from and how the money flows into and out of the system. Social Security is continually funded by payroll taxes from current workers and their employers. Since 2021, the amount of benefits paid to beneficiaries has exceeded the amount of payroll taxes paid into the system.

When there is a difference between the amount of income received versus the incoming payroll tax payments, reserves from the Social Security trust are used to pay the difference. Current projections show that Social Security trust fund reserves will be exhausted by 2033, unless Congress takes additional action. However, it’s important to note that this projection does not mean that all payments will stop in 2033. If Congress takes no action, there will still be enough funds to pay approximately 77% of benefits based on current projections. While this would represent a large cut in benefits, especially for the vast majority of workers who rely on Social Security payments as a primary source of income, it does not mean that all funds will be depleted by 2033.

In the meantime, Congress could decide to increase revenue by raising taxes or removing the FICA tax limit on higher-earning Americans. If no legislative solution is reached, then beneficiaries will experience a 23% pay cut after 2033, but this situation is not the equivalent of “Social Security running out of money” to pay benefits checks.

In addition to age demographics in the United States, income inequality plays a role, since payroll tax rates have not changed since 1990, while a larger share of higher-earning workers have less of their total wages subject to Social Security taxes. This is due to the Social Security payroll cap of $176,100. Any amount of income above this cap is not subject to payroll taxes. Forty years ago, 90% of income was subject to Social Security payroll taxes. Currently, that percentage is at 83.

As the trust fund runs low, one solution is to raise the cap on Social Security payroll taxes to add more funds to the general trust account, which would only impact workers earning above $176,100 in annual income. Other solutions include cutting benefits from other programs to fund the shortfall, or by pursuing a mixture of cuts to programs and progressive tax increases.

While no one has a crystal ball, and the political situation can always change, most Social Security observers view progressive tax increases through raising the FICA tax on wealthier workers as a relatively straightforward solution to the shortfall. Raising taxes on the wealthiest workers is also politically popular across many ages and demographics, making it easier to envision congressional action in that direction. While Congress is currently incredibly unpopular and has not proven the ability to pass major legislation, the idea that constituents from both political parties will face a 23% reduction in payments without demanding change from elected representatives is hard to envision. Since age and disability are bipartisan, it’s reasonable to presume that some action will be taken by Congress in the next eight years before the 2033 projected shortfall.

While these issues are complex, the pervasive misinformation has real-world implications. The fear of Social Security’s collapse often drives people to consider claiming benefits as early as possible once they reach age 62. This is based on the understandable fear that, if they continue to wait until they reach full retirement age, the retirement program won’t be around anymore. However, this decision has permanent consequences and can lead to substantial losses in benefits income.

When deciding whether to claim early retirement or wait, it’s critical to consider your financial situation, general health, and life expectancy, and discuss the impact of the decision with a trusted financial advisor. This decision should be based on sound information rather than clickbait news coverage.

Myth 2: “Aging Boomers Are Draining Social Security Beyond Repair”

It’s common to hear that the retirement of the baby boom generation is the single cause of Social Security’s financial strain. As the theory goes, too many baby boomers are drawing Social Security checks, depleting the trust fund, and taking more in financial and healthcare benefits than they paid into the system.

The truth is more complicated. While population age demographics do contribute to current pressures on the Social Security trust fund, this narrative oversimplifies the issue and ignores other key drivers of the health of the Social Security fund. Baby boomers are a large demographic who spent many years working and paying into Social Security via their payroll taxes. As this large population reaches full retirement age and claims Social Security, a natural impact is that there will be more outflow in payments, decreasing the reserves in the trust fund.

However, other factors also contribute to the current situation, including lower birth rates and lower overall numbers of working-age people paying Social Security taxes. Also, reducing the number of immigrants in the United States will contribute to the shortfall, as immigrants contribute more Social Security taxes than they receive as a demographic (see Myth 7).

Myth 3: “Social Security Is a Major Driver of the Federal Deficit”

Social Security does not add to the national deficit. The law states that Social Security cannot borrow money to pay retirement or disability benefits. The law also states that Social Security cannot use money from the government’s general tax reserves to pay benefits. Therefore, Social Security does not contribute to the US government’s debt.

Understanding Social Security’s funding mechanism

To understand why Social Security does not contribute to the debt, look at how the program is funded. The money for Social Security payments comes from Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes. The FICA rate is 12.4%, split equally between workers and employers. Take a look at your paycheck: 6.2 percent of your gross income is taken out each pay period to pay FICA, and your employer pays the other 6.2% each period. These taxes are how the Social Security trust is funded. When you pay taxes to Social Security, you are contributing to the benefits of older and disabled people who paid into the system before you. When you retire or become unable to work due to a disability, your monthly payment will be funded by current tax-paying workers.

Why shortfalls do not contribute to the deficit

Projected Social Security shortfalls, such as the 23% benefit cut expected around 2033 if Congress takes no action, reflect a timing mismatch: the projected payroll tax revenue will be insufficient to cover all benefits in that year. This does not mean Social Security is driving the federal deficit. Instead, it signals that adjustments, such as like modifying the payroll tax cap, increasing contributions, or modest benefit changes, may be required to maintain full solvency for the retirement and disability programs.

Myth 4: “The Social Security Trust Fund Is Just a Pile of IOUs”

A widespread misconception is that Social Security is a Ponzi scheme. As this myth goes, the future payments to retirees and disability beneficiaries are paid by current payroll tax contributions. Therefore, like a Ponzi scheme, the “profits” paid from the Social Security trust fund to current beneficiaries are merely “deposits” from current tax-paying workers.

Many politicians and commentators evoke the famous case of Bernie Madoff, who illegally commingled investor funds by using the money from new investor clients to pay out the longer-term investor clients. The “Ponzi” aspect of the Madoff scheme was his use of the new inflow of investor money to pay dividends and profits to investors who had invested with him earlier, rather than maintaining each individual account separately and paying each client with profits from their individual investment. When too many of Madoff’s clients tried to cash out on their investment, Madoff ran out of new investor money to pay these “profits.” Since he had lied about the percentage of investor returns, his fund ran dry and his scheme collapsed.

However, Social Security is nothing like Madoff’s investment scheme. To understand why, it’s critical to first understand how the trust fund works.

How the trust fund actually works: More checking account than hedge fund

The trust fund is more like a checking account than a hedge fund. As with any checking account, when the amount of money withdrawn exceeds the amount of money deposited, the balance of the account decreases. And in the case of the Social Security trust funds, the government of the United States of America is guaranteeing payment on the account, while also paying investment interest to the accounts.

Social Security maintains two trust funds: one for retirement benefits and another for disability insurance. Surpluses are invested in special-issue Treasury bonds, which can be redeemed when revenue falls short of obligations. As of 2024, the combined reserves stood at $2.72 trillion, reflecting decades of accumulated contributions and investment earnings. Surplus funds are used to invest in Treasury bonds, which are redeemed to cover benefit costs. Unlike IOUs, the funds are backed by the full faith and credit of the government, and are viewed as long-term, low-risk investments. Therefore, Social Security is backed by tangible debt securities, far from a piece of paper with the words “I owe you” written on it and nothing else to secure the debt.

Myth 5: “We Must Cut Benefits Now to Preserve Social Security for the Future”

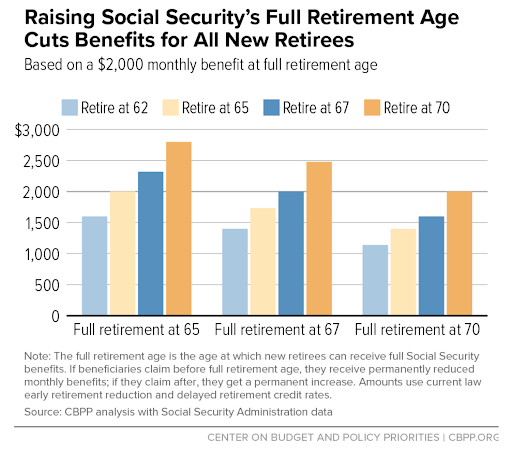

Some argue that reducing Social Security benefits today is the only way to safeguard the system for younger generations. This argument typically calls for raising the full retirement age higher than age 67 when workers can claim their full benefit. As the argument goes, because people are living longer, their working lifespan is longer in duration, and therefore, we should not incentivize people to claim retirement as early as age 62 or receive full retirement at age 67 (for those born after 1960).

While it is true that raising the retirement age would save money, it’s important to note that raising the full retirement age does not impact eligibility for early retirement benefits. The savings from raising the full retirement age come from cutting the average lifetime benefits received for new retirees who claim retirement benefits early.

As can be seen in the figures above, raising the full retirement age results in an across-the-board benefits cut for all retirees, regardless of whether they claim retirement before, during, or after their full retirement age.

Another proposal includes raising the age at which new retirees can claim early retirement. However, this proposal would negatively impact people with lower life expectancy, as they would receive retirement benefits for fewer years and thus have lower lifetime income. Social Security actuarial studies have indicated that such a change would have no cost savings to the Social Security trust fund because forcing people to wait longer to claim retirement would result in retirees receiving a higher benefit for a shorter period of time versus receiving a lower benefit for a longer period of time.

Longevity gains are unevenly distributed

While adjusting benefits is one approach for maintaining solvency, raising the retirement age could disproportionately benefit higher-income workers, especially those who work in office environments, while harming blue-collar workers who work in more physically demanding industries. Advocates for raising the retirement age often point to increased longevity across the population, noting that Americans are living longer and therefore collecting more total benefits; however, this increase in lifespan is not equally distributed. In fact, a recent study suggests that the wealthiest 1% of Americans are living seven years longer on average than the bottom 50% of households in America.

In addition, raising the full retirement age would disproportionately impact women and minorities, who have statistically fewer resources to use for retirement, outside of their Social Security benefits. This means that Social Security is the federal program that is most responsible for reducing rates of poverty in all 50 states.

Myth 6: “Social Security Is Rife with Waste, Fraud, and Abuse”

A popular misconception is that Social Security is plagued by rampant fraud and inefficiency. This myth is often amplified by sensational claims by politicians and people in a position to know better, which get repeated in the media without proper fact-checking. While the program is large and complex, this narrative significantly exaggerates the scope of improper payments and misrepresents how the system actually operates.

The reality of improper payments

Social Security has a payment accuracy rate of over 99%. Such a low rate of fraud would be the envy of major private sectors, including retail, gas stations, eCommerce, and travel/hospitality, which all have a higher rate of fraudulent transactions than Social Security. This demonstrates that the vast majority of funds are correctly distributed to beneficiaries, countering claims that Social Security is dominated by waste and abuse. The low statistics on fraud is even more impressive given the fact that Social Security is operating at the lowest capacity in terms of employees and resources in years.

President Trump and Elon Musk repeatedly claimed that millions of people over the age of 100 were receiving benefits, raising the specter of rampant fraud within the Social Security system. The insinuation from the administration and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) was that these payments were going to some unspecified undeserving recipients, since most people do not live to be over age 100.

While it is true that Social Security keeps a master database of the Social Security numbers of those born prior to 1920, and due to the difficulty of keeping accurate records of all deceased individuals, some people on the list over age 100 were never marked as deceased. But the mere existence of these people’s names on this list does not mean that benefits are being paid to millions of people over the age of 100.

Social Security also has a process for automatically terminating benefits for people over the age of 115, presuming those beneficiaries are deceased unless they respond to SSA notices. While people over the age of 115 are listed on the master death file, their presence on the list does not mean they are currently receiving benefits.

Myth 7: “Illegal Immigrants and Minorities Are Draining Social Security Funds”

The fearmongering about Social Security also has an ugly tendency to demonize specific groups of people: immigrants to the United States and minorities. Similar to the racist and incorrect trope of the “welfare queen” popularized by the Reagan administration, there is a long racist tradition in this country of finger-pointing and raising suspicions about illegal immigrants draining Social Security resources. The claim is based on the assumption that certain undeserving segments of the population are receiving Social Security despite being ineligible. People who know nothing about the Social Security system, how it works, or how it’s funded, will confidently claim that illegal immigrants are stealing Social Security resources, using disproportionate amounts of healthcare and causing hospital wait times to go up, and that is why Social Security funds will be depleted before they reach retirement age.

Not only is this a racist trope, but the literal opposite is true. Illegal immigrants pay more Social Security taxes than they receive in benefits and the taxes they pay prolong the Medicare trust fund. Illegal immigrants cannot qualify for Social Security retirement or disability programs because they do not have a valid Social Security number. Illegal immigrants often work “illegally” by taking someone else’s Social Security number in order to obtain employment. In this situation, Social Security taxes are deducted every month from the paycheck through FICA. The illegal immigrant working in this scenario is therefore paying FICA taxes that fund benefits for the disabled and retired throughout the country, benefits they will never claim for themselves when they reach retirement age.

For example, in 2022, illegal immigrants contributed $25.7 billion in taxes and yet were unable to claim any benefits from the Social Security Administration. Many analysts who study Social Security trust fund statistics cite the deportation of illegal immigrants as a reason for the trust fund running out earlier than initially forecasted. Similarly, legal immigrants contribute more FICA taxes than they receive in benefits, due in part to the fact that legal immigrants are often younger people who work and require less healthcare, so their presence is a net positive for the funding of the Social Security system.

From rumors about the program “going broke” to misleading claims about who qualifies, Social Security is surrounded by myths. LaPorte Law Firm is here to set the record straight. Learn the facts from our experienced professionals — schedule a free consultation today.

FAQs

No. While the trust fund reserves may be depleted around 2033 if no changes are made, ongoing payroll tax revenue will continue to fund a substantial portion of benefits — about 77% — ensuring the program remains functional even during a shortfall.

Not entirely. While demographics contribute to pressures, factors such as lower birth rates, income inequality, and the payroll tax cap play equally significant roles in the program’s financial challenges.

No. Social Security is primarily funded by payroll taxes and interest on trust fund investments. By law, it cannot borrow from the federal budget to pay benefits, making it largely self-contained.

No. Social Security is more like a checking account. The trust fund holds special-issue Treasury bonds backed by the full faith and credit of the US government. These bonds are real financial assets and are used to pay benefits when revenue falls short.

No. Less than 1% of the more than $1 trillion in annual benefit payments are considered improper. The system operates with strong oversight, and most claims of fraud or mismanagement are exaggerated.